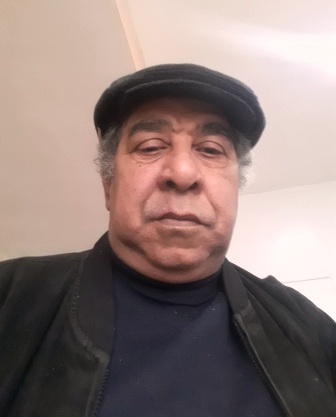

Muath Al-Samei (The Forgotten Poet in the Geography of Text)

Mohammed Al-Mekhlafi –Yemen

Through a private interview with the Yemeni poet Muath Hamid Al-Samei I came to uncover the contours of a profound journey—one never paved with roses, but one that often resembled a walk through the realm of jinn.

It is not easy to be a friend to everything except yourself, he began, convinced that thought offered truer companionship than people. Yet he soon discovered that the shortest path toward his own being was strewn with rugged obstacles—entering it was no less than wandering through the wilderness of jinn.

Muath descends from a world as tumultuous as the very edges of defeat and disappointment. He hails from Sanamat, his birthplace, a name heavy with strangeness and endless longing. The village lies east of Mount Saber, in the district of Al-Mesrakh, Taiz Governorate—small as a literary text, crouching at the hill’s edge “like an aged eagle,” as he describes it, cradling both the sun and the clouds.

In this place, he grew up in a home that mirrored his own being: an old rural cellar, so low that one could scarcely stand upright beneath its ceiling—more a hut wedged into the throat of stone. There he shared life with his family, with God, as he says, “with two stars that outgrew him at nightfall, with the pulse of his mother, with cold and wind and sun and rain, and with his father’s hands dampened by the sweat of the fields.”

From his earliest years, his grandfather and father taught him fragments of the Qur’an, Hadith, wise sayings, and inherited verses of poetry. Despite his frequent rebellion and the punishments that followed, they instilled in him the first principles of reading and writing, before sending him—reluctantly—to Al-Majd Preparatory School in the village.

The school was no better at nurturing knowledge—or perhaps he was not ready to receive it. The only path along which he felt true desire and delight was that of eloquence, poetry, and the oral stories passed down through memory. The composition class became his quiet refuge amid the noise of school life, especially when the subject was open-ended and granted him the freedom to soar.

This singular inclination pleased his grandfather, a man with deep passion for eloquence and literature, though it angered others. During his preparatory years, another figure left a lasting mark: an Egyptian teacher named Hassan, who would read Muadh’s compositions aloud before the school assembly and gently tell him, “You are a poet.”

At this tender age—before he had even reached thirteen—Muath was married, driven by family circumstances and the pressure of customs which then, and in some measure still today, demanded such arrangements. Around the same time, he stumbled upon a hidden treasure on an old shelf in his grandfather’s house: Diwan of Al-Shafei the mystical writings of Ibn ‘Alwan, and a manuscript containing the verses of Al-Ma‘arri and the tales of Abu Nuwas. He devoured them with the hunger of a captive, inscribing them upon his heart.

Secondary school brought him no better fortune. It tore him between two far-flung institutions: Al-Janad Al-Nejada School and Al-Enqadh Al-Serari School. Each day he traversed long distances along paths of “frost and fire,” as he described them, gaining little but the endurance of sprinting across mountains and valleys.

It was during this restless period that he began his first true attempts at writing. He scribbled verses on scraps of paper, in the margins of books, even on cigarette packs. Rarely did he share them, save with his closest friend and “that snub-nosed girl” of his childhood—“the wonder of his past and the mother of his poems forever”—who once told him one evening: “A man cannot be a true lover until his fingertips drip with poetry and songs pour from his lips, colored like birds.”

When he finally dared to share his poetry with a wider audience, he was met with mockery and accusations of plagiarism. The rejection crushed him, driving him to tears of anguish, until he withdrew into silence.

Yet a decisive turning point awaited him. Some of his verses reached the eminent poet Mohammed Saeed Abdullah—“the finest and most eloquent voice in the entire region,” as Muadh recalls. The great poet, with all his stature, descended into the boy’s humble room, sat with him as an equal, stroked his head like a prophet, and said: “You are a true poet, my son. You need only to embrace the experience with courage and boldness. Fear no one.”

That day, Abdullah gifted him a bundle of books: volumes of love poetry, the complete works of Al-Mutanabbi, and pamphlets of Al-Baradouni. From then on, he nurtured Muadh with love, poems, and letters, until death carried him away. “I am indebted to no one after my father,” Muadh says, “as I am to this man.”

After completing secondary school, he was drafted into two years of compulsory service. That period left a deep imprint on him, granting him ample time for reading in a nearby library overseen by a kind-hearted man who, as Muath puts it, “opened his heart before he opened its shelves.”

In 2002, Muath left his village—with all its beauty and misery—for the city. There he struggled to balance supporting his family with completing his university studies, but faced many obstacles. Two years later, he embarked on a journey abroad, seeking new experiences, opportunities, and a deeper understanding of the estrangement he had already felt in his homeland.

Life abroad brought both hardship and reflection, and his poems grew heavier with affliction. He labored in various trades, yet devoted every free hour to the Obeikan Library, where he met poets and literary enthusiasts. It was there that he took his first steps onto the international literary stage—receiving an invitation to a literary conference in Tunisia. For days, he mingled with poets, writers, and artists, and for the first time felt he was standing on the threshold of his rightful place in the world.

In 2012, Muath Al-Samei made the decisive choice to return from abroad. That return carried both the heaviness of life and the essence of resurrection. Soon he realized that his educational and cultural grounding was too fragile to sustain him, and so he resolved to begin again from the very roots. Within two years, he harvested more than all the government schools, across their three stages, had ever offered him.

During this period, he frequented cafés and informal literary forums, where he found companions who “washed their faces in words and hung delirious poems upon the damp walls.” At the dawn of 2014, he received a gracious invitation from Professor Mohammed Farea to stand upon the stage of Al-Saeed Cultural Foundation—the country’s foremost literary forum—side by side with the grandest of poets. That evening he won first place in the “Alaq” competition for classical poetry at the city level.

Soon after, fate smiled on him again, this time through luminous figures such as Engineer Abdulkarim Al-Noman and poet Yasin Abdulaziz, who took him by the hand, pruned his gardens, nurtured his seedlings, straightened his bent frame, and lifted him upward.

He began to feel the intoxication of presence and to touch the literary scene in earnest—until “the sky fell” with the onset of war in 2015, which brought his first displacement. Aden was not a final refuge. He returned to his village, but found no space wide enough to contain his brokenness. “At the end of 2015,” he recalls, “it kicked me toward the sea—perhaps thinking the ocean more capable of containing corpses.”

Through all this journey, Muath remained that forgotten man in the geography of text, a figure without fixed form, for “with every five defeats his features and habits change.” He practices the rituals of writing with effort—stumbling, leaping, falling, flying, bowing, standing again. He is the offspring of that enigmatic bond between poet and man.

He fled early to poetry, though without knowing from what he fled: perhaps from himself and his desolate childhood, perhaps from the false promises of tomorrow, or from the doubts and forgotten games of his first beloved. In time, he grew accustomed to solitude, like “a wandering monk fading on the banks of letters, swatting away the blackness of dusk with his disappointments, and prodding the sky with his broken dreams.”

For him, writing is less a craft than a spiritual necessity. He inhabits the text in all its molds and forms, with its eternal contradictions that mirror human relations, and with its renewal as a creative eternity of hidden correspondences.

Despite all he has written, Muath remains convinced that he has not yet begun, and that what he has published is nothing more than a handful of first attempts—mere beginnings, nails we stumble upon in the crowds of tomorrow. Among his works are Love and War, Many Tears for One Feast, and most recently, his collection The Curse of the Keyboard, published in Beirut under the patronage of Adonis, within Eshraqat series of Abaad Publishing and Distribution House.

Still, he carries many projects within him. For years he has labored over a long novel manuscript—his true narrative voice—alongside another novel set aside for a time, and two poetry collections in progress: An Ambush in the Air and Metallic Longings.

For Muath, the human being is the first key to humanizing the surrounding world, and this is his pursuit: nothing beyond humanizing himself. Writing, for him, is not the hunt for words. Rather, it comes “as a jinni, in a call that crosses imaginations and eras, in a message whose rain is unexpected, in a fleeting visit like lightning that sparks the seedlings of grass in his depths.” The text ambushes him and slips away, while he pants after it, careful not to stumble into the mire.

For him, writing is a strange window, filled with life yet inhabited by death—a place where we cast our disappointments with the elegance of a wolf in rainy daylight, if only to wound the generations to come.

Life itself was his first and harshest teacher. Every loss transformed into a poetic breath; every moment of fragility left behind a sentence he would never have written otherwise. He reads widely, not to imitate but to discover his own boundaries, and every poet he encountered became a mirror reflecting another face of himself.

He believes it is Arab conventionality that charts our paths, and that the Yemeni literary scene is but a mirror of the fragmented Arab world scattered across the map. True change, he insists, lies in the hands of the contemporary poet of diverse sources—one who cares less for form than for substance, for it is the idea that dictates the form through which it erupts.

And though poets are often described as visionaries or prophets, he believes they must know—by creative instinct—that they are not mere transmitters of reality, but its destroyers and rebuilders. To achieve this, they must pass through two conditions: first, the complete dismantling of the present reality; and second, the reassembling of its elements in a manner closest to liberation—within and without.

Such is Muath Al-Samei: a poet still searching for his path, trimming the vines of poems that climb the sidewalks, carrying within him the eternal contradiction between man and poet, between flight and confrontation, between the cellar and the poem.

From his latest collection The Curse of the Keyboard:

The Curse of the Keyboard

You drift through my mind like a text.

I have grown weary of loving you in the old ways,

with the worn-out gestures of bygone lovers.

I am tired of loving you with the languor of Jamil and Buthayna,

with the exhaustion of Qays Ibn Al-Mulawwah,

with the timid mirrors of Romeo,

with the sword of ʿAntarah—

a blade that cuts nothing

but our throats on paper.

Love, my willow, has become a commodity,

faded, counterfeit.

The sword of ʿAntarah is no longer fit for battle,

nor even for the kitchen—

a knife unneeded

to slice an onion.

So let me search for a way to love you

beyond the walls of our village, crowded with rifles and barricades,

beyond our tribes, branded

by the cough of night and the rule of boys,

beyond this sky so swollen

with fangs and nails and masks.

Let me search for a way in which you are water,

and I am wind—

the wave, the hill, the storm.

A way to love you

with the audacity of a mufti,

the innocence of a wolf,

the hardness of ice,

the certainty of thorn.

To love you with the multiplication of bacteria,

with the permanence of bilharzia,

with Corona’s invasion of the planet’s pockets.

To love you in the manner of the night,

in the manner of clouds,

in the manner of lanternfish

glimmering in distant oceans.

A way more reckless than Barça’s crowds,

more feral than the claws of tigers,

stranger than Camilo lost

on the edges of the universe.

Tell me—

what would you say

if I tried the way of Emmanuel Macron and Brigitte Trogneux,

and loved you only for a while?

I find it madder still,

and fraught with peril.